Ammunition has changed a lot over the centuries. From using crude chunks of lead or other metal in the earliest muskets to the precision-engineered cartidges we use today, there has been a steady and progressive improvement. However, from the earliest cannons of 12th Century China to the sleek semi-automatics of today, the basic principle remains the same. The basic concept is using a powder charge to launch a projectile at the target.

From the first Jaeger rifles of Prussia, through the flintlock muskets of the 18th and 19th centuries, until after the American Civil War, the bullet was a separate, molded piece of lead that needed a powder charge to fire it. a shooter had to manually pour powder down the muzzle, and pack it down with a wa d of cloth, and a bullet. They then had to add powder to the pan to be ignited by the flintlock mechanism. This was improved somewhat beginning in the 1840s when percussion firearms came onto the scene. With a percussion firearm, the pre-measured charge of powder was contained in small sacks of nitrated paper or cloth, and the bullet packed on top of it. Rather than pouring powder in a pan to prime the charge, there were tiny, thin brass or copper bowl-shaped percussion caps, filled with fulminate of mercury that were stuck onto cones or "nipples." Each of these nipples had a tiny hole in them, and when the firearm's hammer struck the percussion cap, a spark would flash through the hole, igniting the main charge. At the time, they didn't know it, but percussion firearms were a short-lived technology that paved the way for rapid advances in firearms development. They bridged the short gap between flintlock weapons and today's fully automatic weapons.

For a brief period in the later part of the 1800s, there was a type of cartridge called pinfire, These cartridges had a tiny pin sticking out from the side of the cartridge base. When struck by a hammer or other striking mechanism, it ignite the primer and the charge. This is a lot less safe and reliable than the centerfire rounds we use today, and did not last very long. A small number of firearms, including some old Derringer pocket pistols in small calibers used the pinfire cartridges. During the short reign of percussion firearms, the small sacks of nitrated paper were sometimes referred to as "Paper Cartridges."

In 1860, gunsmith Benjamin Tyler Henry perfected a fully self-contained metal rimfire cartridge that had been recently invented by Daniel Wesson, and put it to use in his own invention, the lever action rifle. Like most new things, it was a little slow to catch on. This was a time when most shooters were still using muskets, rifled muskets, or percussion revolvers, and the use of rifles--or full metal cartridges--was in its infancy. By the early 1870s, the use of full metal cartridges was growing steadily and replacing the old lead bullets used in flintlock firearms.

Starting with the .44 caliber rimfire cartridges used in the 1860 Henry Repeating Rifle, development of centerfire cartridges quickly followed. At the same time, the technology of ratcheting semi-automatic revolvers was also improving rapidly, resulting in the runaway s uccess of the Colt Single Action revolvers which were soon in very widespread use. This was also about the time that the old black powder was being replaced by the new smokeless powder. By the end of the 1800s, a new kind of feeding system was being developed which would once again revolutionize firearms technology, the use of cartridge clips, followed almost immediately by the use of box magazines. This was about the time such legends as the Mauser C96 and Colt M1911 were making their debut.

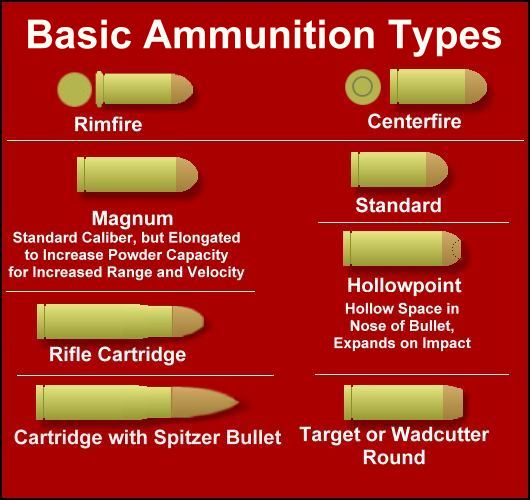

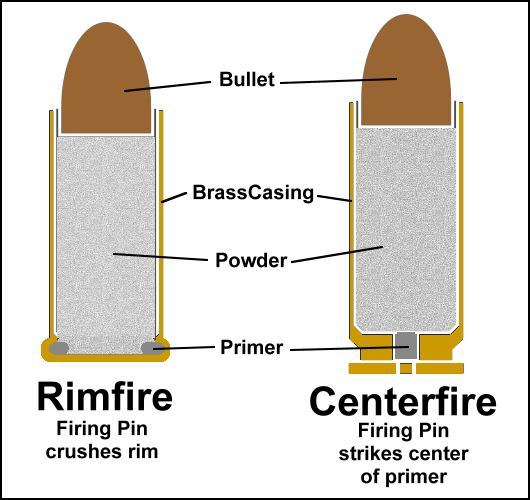

By this time, full metal, self-contained cartridges were in widespread use, and are still in use now. Today, rimfire cartridges are mainly only used in small ammunition, such as .22 caliber cartridges.

A rimfire cartridge has the primer located in the rim, at the base of the cartridge. The firing pin or striker then strikes the cartridge, crushing the rim and the primer inside of it, which in turn ignites the powder. With a modern cartridge, the powder charge explodes, blasting the bullet off of the end of the cartridge. With a rimfire cartridge, the rim is crushed, and the casing can no longer be used. With a centerfire cartridge, the casing can be reused, if you have the equipment to replace the powder, primer and the bullet on the casing. This is called handloading or reloading, but requires special equipment, and can be dangerous unless you are experienced in doing this. The main reasons for doing this are to reduce the expense of buying new ammunition, (especially these days!) and that handloading allows you to have more control over the quality and finish of your rounds.