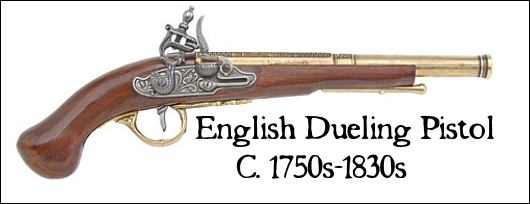

18th Century English Dueling Pistols, and a look at the history and culture of dueling.

Duels go back at least to 11th century medieval Europe and have gone through some changes. Each culture had their own rules of engagement and customs. While medieval European duels were fought with sabres or swords, the practice of using pistols came about in the 1600s. In the early 1700s, dueling was illegal in parts of Europe, but laws did not seem to diminish the practice. Dueling was not for everyone, but reserved only for those in high standing. You had to be of noble birth, or otherwise be considered a "gentleman" in order to even qualify to settle a dispute or prove/reclaim honor by way of a duel. This generally meant that you had to be either wealthy, powerful, or both. Even in cases where dueling was illegal, there was often no prosecution, the offenders being too high ranking or untouchable to punish. In a duel, each person was accompanied by at least one person, called a "second." Prior to the 1600s, not only did the dueling parties have to duel, but their seconds as well.

In most European societies, it was disallowed for a person of lower class to challenge someone of upper class to a duel, and vice versa. For a nobleman to even consider a duel against a lower-ranking person was a dishonor in itself. Any person of lower standing who had committed offense to a nobleman was usually just beaten with a cane by a nobleman, or one of his servants, and dismissed. The general idea behind dueling was for an offended nobleman to protect his honor by challenging the offender to a duel. Once the duel was fought, the issue was meant to be considered resolved, regardless of the outcome. It was common for a place and time to be agreed upon, usually in some isolated place, away from crowds or prying eyes. Especially in cases where the practice was banned by the local government. Going back through the ages, there were many different rules of engagement and forms of etiquette. Since 17th century European culture, it had standardized into the duels that most people are now familiar with.

After a slight, insult or dishonor (real or imagined) the offended party would challenge the offender to a duel. This could be communicated verbally, or by removing a gauntlet (glove) and throwing it at the offender's feet or in other ways. If the challenged picked up the gauntlet, that was taken to mean that they agreed to a duel. This is where we get the term "Throwing down the gauntlet." There were also cases of slapping the offender across the face with the gauntlet, in particularly bitter cases, but was not common. Unlike what you may have seen in the media, duels were not always to the death. There could be different terms agreed to by both parties. Often, just drawing first blood was enough to satisfy the duel. Or until one party was no longer able to fight. Sometimes, one or even both duelers would intentionally miss, and the issue would be settled without bloodshed. In dueling with pistols, the general rule was one shot each, and only one shot, unless another arrangement was made. In using pistols, the most common method was to have the duelers stand back to back, take a preset number of steps, turn and fire, or have a counting of seconds, then turn and fire. Sometimes the duel was initiated by having a neutral person throw down a handkerchief, signaling the duelers, already facing each other, to fire.

Dueling began to fall out of favor in the 1800s, has declined sharply to the point of extinction, and is illegal almost everywhere.

The most famous duel fought on American soil was undoubtedly that between sitting Vice President Aaron Burr and Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton. It was a duel that very likely changed the course of American history.

Aaron Burr was a hero of the American Revolution, a

brilliant man and an astute politician, with many friends in high

places. Whether or not he carried the 1800 election, it is likely he'd

have had a great deal more influence in the course of American affairs,

if not for his fateful duel with Alexander Hamilton.

Alexander Hamilton was also a Revolutionary

hero--co-author of The Federalist Papers and one of the founding

fathers of the new republic on the American continent. A senior aide to

General Washington, he commanded three battalions at Yorktown. He

served in the Continental Congress, was the new country's first

Secretary of the Treasury and a signer of the Constitution. He quickly

became one of its foremost authorities on constitutional

interpretation, possibly the first American constitutional lawyer.

Who can say what contributions these two brilliant

and capable men might have made to the new republic, and what path its

history might have taken, if not for the fateful duel that ended in the

death of one and the disgrace of the other? Either or both of them may

well have become president of the republic during their lives.

The two men held such conflicting political views

that it was inevitable they would clash, but the enmity between them

intensified during the bitterly contested election of 1800. After a tie

in the electoral college in which Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr each

received 73 electoral votes, it became the task of the House of

Representatives to finally decide--after the casting of thirty-six

separate ballots--that Thomas Jefferson would be president, and Aaron

Burr Vice President.

It was rumored at the time that Hamilton had more

than a little to do with Burr's

being denied the Presidency, actively

working behind the scenes to ensure his defeat. It was certainly no

secret that Hamilton reg

a

rded Burr as a dangerous fanatic whose views

on monetary policy and government were little short of lunacy. But it

wasn't until 1804, just before Burr was defeated in his bid to become

governor of New York, that a New York newspaper quoted Hamilton as

saying that Burr was ". . . a dangerous man . . . who ought not to be

trusted with the reins of government."

Burr sent Hamilton a

letter demanding he apologize and retract his remarks, and there

followed an acrimonious correspondence in which Hamilton refused, after

which Burr challenged him to a duel, and Hamilton felt honor-bound to

accept. Since dueling had been outlawed in New York, the Burr and

Hamilton parties rowed across the Hudson River in separate boats to a

site known as the Heights of Weehawken, a river landing beneath the New

Jersey Palisades which had become a popular dueling site of the day.

The pistols were transported inside a traveling case, and the oarsmen

instructed to stand with their backs to the duelers, so they could say

under oath, if called upon to testify, that they had seen no

pistols--precautions that were probably for naught, given the outcome

and the prominence of the duelers.

Some scholars have said Burr was homicidal for

issuing the challenge, others that Hamilton must have been suicidal for

agreeing to the duel. Still others have said both arguments were true.

The duel was fought with a pair of matched flintlock

pistols made by London gunsmiths Wogden and Barton. By a bizarre

coincidence, the same pistols had been used in several previous duels,

including another involving Aaron Burr, and, more significantly, one in

which Hamilton's oldest son, Phillip, had been killed in 1801. In an

eerie foreshadowing of his father's death to come, Phillip had been

fatally wounded after declining to fire on his opponent, reportedly due

to regret for the part he played in provoking the duel.

Did Hamilton, upon seeing the pistols to be used in

the duel with Burr, recognize them as the same matched pair that had

led to the death of his son? If so, surely the realization would have

made it difficult for him to pick one of them up, deliberately aim and

hold it steady enough to have any hope of hitting his target. Or did

the memory of how his son died so cloud his mind that he was unable to

adequately defend himself? History does not record the answers to those

questions, but it is likely that Phillip's death was strongly on his

mind that day, and may well have been a factor in Hamilton's fatally

odd behavior during the duel with Burr.

Hamilton fired first, but his shot went high in the

air, leaving Burr untouched. Some accounts claim the pistol he used had

a "hair" trigger that caused the weapon to discharge prematurely,

spoiling his aim. Others suggested that Hamilton resolved in advance to

deliberately "throw" (miss) his shot, giving Burr a chance to pause and

reconsider, and that he did so because of his own religious convictions

against taking a life. A letter he wrote to his wife before the duel

affirmed that he would rather have died than to live with the guilt of

taking another’s life.

When it was Burr's turn to fire, however, he

exhibited no such qualms. Taking deadly aim at Alexander Hamilton, he

pulled the trigger, striking his opponent in the stomach. Hamilton was

carried to a friend’s house on Manhattan Island with the ball from

Burr's pistol still lodged in his spine. He suffered agonizing pain

before dying of the wound a day later.

Burr was charged with murder in New York, where he

lived, and in New Jersey where the duel took place, but neither charge

was ever brought to trial. He completed his term as vice president, but

his reputation never recovered. His political career in ruins, he

migrated west. Scandal continued to follow him until his death in 1836.

Flintlock firearms have a slight but noticeable

delay between

pulling the trigger and the actual firing. In a duel, it was required

for each party to have the exact same weapon, with the exact advantages

or disadvantages, in order to offer the involved parties a fair duel.

Since a duel required a fair and perfectly matched set of weapons, the

pistols were made in matched sets of two, to exacting standards of

accuracy. The pistols used in the fatal duel between Alexander Hamilton

and Raymond Burr were the British-built models by the London gunsmith

firm of Wogdon & Barton.

The pistols used in the duel still survive today. They changed hands

several times before being purchased by the Chase Manhattan Bank in

1930, and today remain on display in a Manhattan branch of J.P. Morgan

Chase and Company.

Firearm Type:

Flintlock Dueling Pistol (matched pair)

Nation Of Manufacture: Britain, United

States

Period of Use : 1600s-1850s

Variations: Various. Matched sets of 2

pistols

Ammunition: Lead Ball (Various calibers)

Wars: 2 Gentlemen in high standing, Each

defending their honor

Recent Prices at Auction for Originals: US

$5,000-$20,000 (Rare)

Interested in a pair of authentic replica Dueling Pistols?